- Home

- »

- Germany

- »

- Berlin

- »

- Museum Island

- »

- The Berlin Egyptian Museum

- »

- The Berlin Egyptian Museum - Behind the Scenes

Behind the Scenes

Behind the Scenes of the Egyptian Museum

In any large museum, the public exhibition rooms represent only the tip of the iceberg. There is far more activity going on behind the scenes. About 800 artefacts are on display for the public in Berlin’s Egyptian Museum. But the museum’s storerooms contain more than 100,000 individual pieces. A large staff is responsible not only for maintaining and preserving that enormous collection, but above all for making it accessible for scientific research.

Dietrich Wildung, Director of the museum from 1989-2009:

“A museum participates in documenting historical fact mostly with its research work. That means research in its own storerooms and on the exhibits. But ideally, research also means acquiring new historical materials with fieldwork. In our case, in the Nile Valley, whether that’s in Egypt or, as is currently the case for the Berlin Egyptian Museum, in Sudan, Egypt’s neighbour to the south.”

Karla Kroeper, expedition leader in Naga/Sudan:

“Basically, we work on the digs from January until about the end of March. The beginning of January is the best time for us, with relatively cool temperatures ... about 25 degrees Celsius. By the end of March we have to suspend the excavation work, because it will usually be as hot as 50 degrees in the shade, which is too hot. Even the Bedouins start to sweat.”

No easy undertaking. The geographic location doesn’t make things any easier either. The digs are in the middle of the African steppes, about 100 kilometres from the nearest city, in areas lacking all infrastructure. The endless vast expanse makes it seem as if just a moment has passed since the spectacular expeditions of yesteryear.

Karla Kroeper:

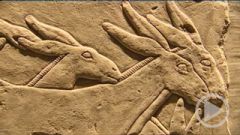

“The Temple of Amon was almost completely buried in sand. All you could see on the surface, basically, was the top edge of the great gates and the head of a ram. As you can see here, the rest of the rams were completely buried when we started digging in Naga.”

After two years of intensive work, the unearthed rams once again gaze proudly across the desert. In order to uncover them, a wall of sand more than two metres high and 50 metres long had to be carted off in baskets. But it was well worth it.

Karla Kroeper:

“When we find something, it’s an exciting moment for us. The tendency at that moment is to want to look at it right away. It’s probably one of the most difficult moments in the life of an archaeologist. When something appears, it first has to be measured, to document how high it is and how deep it’s buried, so that we can later reconstruct the exact initial location in our documentation. Then, of course, it has to be uncovered very, very slowly before you can actually, finally hold an object in your hands.”

When archaeology was still a young science, the expeditions often resembled plundering sprees, with the treasure hunters lining their own pockets and filling the museums of European capitals. These days, archaeology is more about gaining new knowledge than accumulating treasure. But the occasional piece still makes its way to Berlin. Finds are either bought from art dealers, or divided between the home state and the foreign archaeologists – as was customary until 1984.

However they arrive here, the first stop is the Egyptian Museum’s real treasure chamber: the storerooms. At the moment, there are ten of them throughout Berlin. They contain all the antiquities acquired over the last 150 years, sorted by raw material. For instance, the basement of the Pergamon Museum holds the storerooms for stone statues and figurines of all sizes and from all periods.

Within the individual storage depots, the objects are sorted by group. For instance, these containers, called canopic jars, make up one group.

Frank Marohn, museologist at the museum:

“The canopic jars were an important part of the funerary rites. During mummification, the deceased’s embalmed viscera were removed and put in these jars. After the top was put on, the jar was placed in the tomb with the deceased.”

The Berlin collection contains more than 100 individual canopic jars. Each one carries an inventory number. With that number, all the information relevant to a specific piece can be called up from a central database. Where it’s located, of course is very important. Each set of shelves and each shelf has a unique number. For instance, this is the second shelf in shelves 542. There is also a colour coding system that provides additional information about each piece in the collection.

The metal storerooms are a perfect example of the importance of a methodical archiving system. The metal section is filled with countless, small, precious objects. There are several hundred bronze statuettes of the god Osiris alone. The deceased was entombed with many burial objects to ensure a safe journey to the afterlife.

The mummies are the mystical highlight of ancient Egyptian culture for many visitors to the museum. The Berlin museum’s storerooms contain about 60 mummies from all the various periods of Egyptian antiquity. Mummies are particularly sensitive to environment. The mummy storerooms must be maintained at a constant temperature of 20 degrees centigrade and 45 percent humidity.

The fact that the mummies have remained so well preserved after thousands of years is a tribute to the skill of the Egyptian embalmers – and to their deep faith. The mummification ceremony itself was taboo for the Egyptians, and the mummies lay deep in their tombs, shielded from the eyes of the living. Nor was it only pharaohs and high functionaries who were embalmed for eternal life in the hereafter.

Frank Marohn:

“In addition to a large number of human mummies, the Egyptian Museum also has a lot of animal mummies. For instance, this little cat, where even the ears and the eyes have been perfectly formed. There are also mummies of crocodiles. The crocodile mummies can be wrapped up and they look like this. But there are also unwrapped ones that look like this. The animal mummies represent personifications of Egyptian gods.”

The same strict guidelines for storage conditions apply to the mummies as to the other objects made from organic materials. Here, in the wood storerooms, the temperature is strictly controlled. It’s only thanks to the constant temperatures in the hermetically sealed tombs that the wood and other organic materials have survived down the centuries.

The museum has a number of in-house restoration and maintenance workshops to take care of its inventory.

Margret Pohl, restorer:

“The Egyptian Museum’s wood workshop takes care not only of wooden objects, but of all the Egyptian Museum objects made of organic materials. That includes ivory, paper, plant materials and even, for instance, shells.”

A restorer’s job covers a lot of ground. In addition to restoration, they’re also responsible for making sure the objects are properly stored. That includes climate control, documenting their condition and taking care of pieces on public display. In restoring and taking care of the antiquities, they must develop an individual strategy for the optimal treatment of each “patient” using the most up-to-date scientific methods. Often, the legacy of earlier attempts to treat a piece presents a problem.

Franziska Doetzl, restorer:

“You can see here that large sections of putty were used during an earlier restoration and the original coloured piece, was attached to that. The result was that the original shape was slightly distorted. The current method of restoration is to remove the putty, which you can still clearly see here, and to try to go back to original methods of connecting the pieces. Here you see a hole for a dowel; there’s one on the other side too. So you can manufacture a new dowel and use it to join them. That’s the original method.”

Gisela Engelhardt, restorer:

“These objects were created during the period between 5000 B.C. and about 1000 A.D. And each and every one of them is awaiting restorations at some point. This relief is from the Amarna period. I worked on it for weeks and months. This is a 'before' picture. You can see quite clearly that the stele was broken into four large fragments. On the side, there are some smaller fragments that were glued back on later."

While I was restoring it, I discovered the technique used to paint it. The slab, in this case limestone, was ground down, evened out. Then the scene was sketched out with pink outlines. Then the relief was etched and a yellow background was painted on – right into the red frame. The final colours were painted on top of the yellow.

The scene itself is unusual; it shows a Syrian drinking beer. To see a Syrian in Egypt was very unusual. He would have been immigrant labour, so to speak, and this was a kind of memorial stele. In other words, after he died a plaque was done for him. But as a foreigner, a Syrian wouldn’t have been able to assert himself with the Egyptian gods of death.” Like solving an immense jigsaw puzzle, cooperation between all the divisions of the Egyptian Museum – the workshops, the storerooms and the archaeological expeditions – produces an ever clearer picture of the life and culture of ancient Egypt.